On April 26, U.S. President Joe Biden welcomed South Korean President Yoon Suk-yeol to the White House for a summit meeting to celebrate the seventieth anniversary of the U.S.-South Korea alliance and open a new chapter for the next seventy years of expanded cooperation. Amid a substantial list of topics discussed by the two leaders, extended deterrence emerged as the top deliverable.

China Primer: South China Sea Disputes

China Primer: South China Sea Disputes

China Primer: South China Sea Disputes

Overview

Multiple Asian governments assert sovereignty over rocks, reefs, and other geographic features in the heavily trafficked South China Sea (SCS), with the People’s Republic of China (PRC or China) arguably making the most assertive claims. The United States makes no territorial claim in the SCS and takes no position on sovereignty over any of the geographic features in the SCS, but has urged that disputes be settled without coercion and on the basis of international law. Separate from the sovereignty disputes, the United States and China disagree over what rights international law grants foreign militaries to fly, sail, and operate in a country’s territorial sea or Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ).

Since 2013, the sovereignty disputes and the U.S.-China dispute over freedom of the seas for military ships and aircraft have converged in the controversy over military outposts China has built on disputed features in the SCS. Observers viewed the military outposts as part of a PRC effort to project military power eastward from its coast and contest U.S. military supremacy in maritime East Asia. Much of China’s military modernization is aimed at developing capabilities to deter or defeat third-party intervention in a regional military conflict. (For more on China’s military, see CRS In Focus IF11719, China Primer: The People’s Liberation Army (PLA), by Caitlin Campbell.) Observers have been alert to other actions China might take to dominate the SCS, including initiating reclamation on another SCS geographic feature, such as Scarborough Shoal, or declaring an Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ) over parts of the SCS.

The last several Congresses have focused on China’s efforts to use coercion and intimidation to increase its influence, including in the SCS, and passed legislation aimed at improving the ability of the United States and its partners to protect their interests and freedom of navigation and oversight.

Key Facts

The SCS is one of the world’s most heavily trafficked waterways. An estimated $3.4 trillion in ship-borne commerce transits the sea each year, including energy supplies to U.S. treaty allies Japan and South Korea. According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, the SCS contains about 11 billion barrels of oil rated as proved or probable reserves—a level similar to the amount of proved oil reserves in Mexico—and 190 trillion cubic feet of natural gas. The SCS also contains significant fish stocks, coral, and other undersea resources.

The Sovereignty Disputes

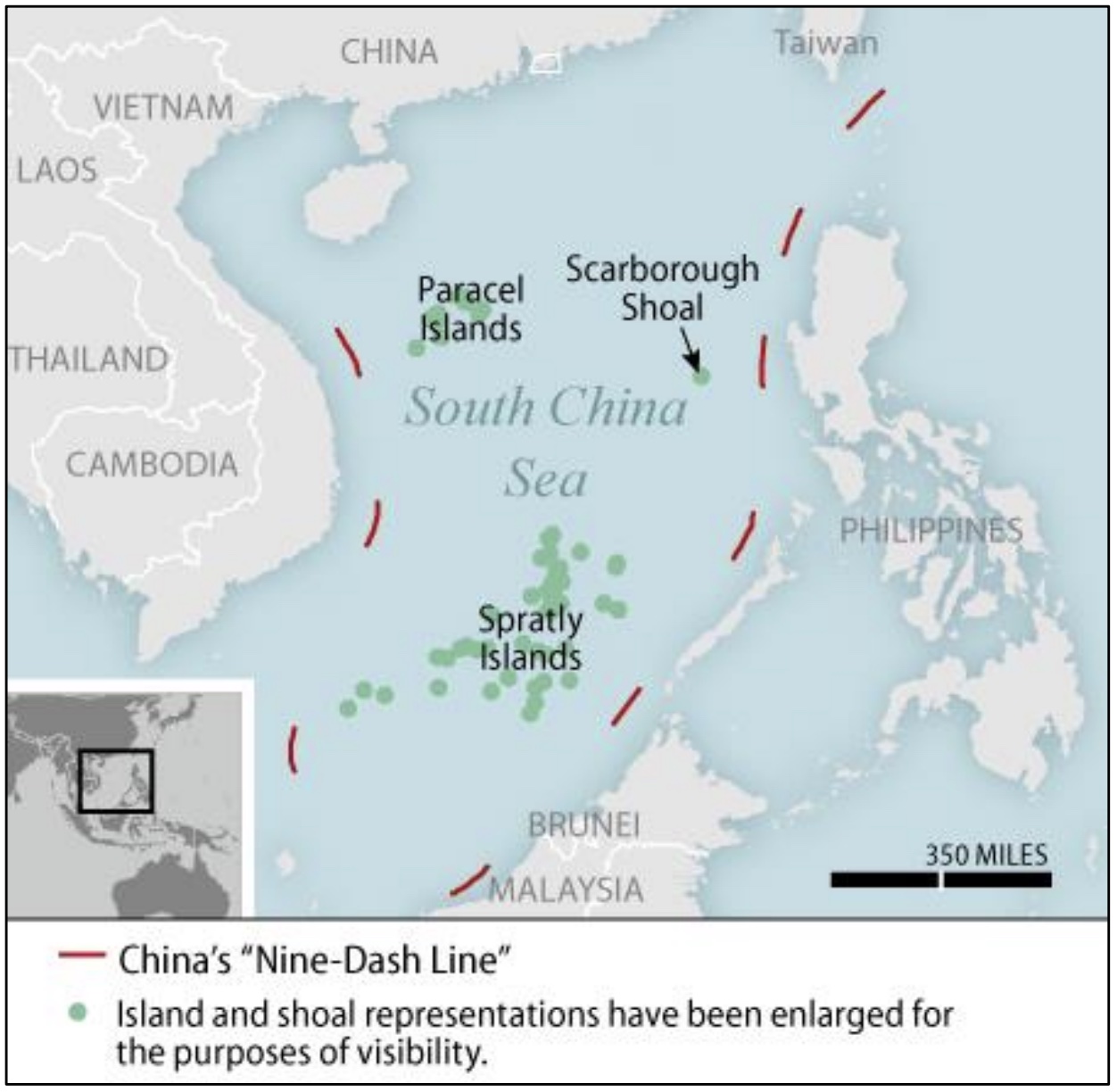

China asserts “indisputable sovereignty over the islands in the South China Sea and the adjacent waters” without defining the scope of its “adjacent waters” claim. On maps, China depicts its claims with a “nine-dash line” that, if connected, would enclose an area covering approximately 62% of the sea, according to the U.S. Department of State. (The estimate is based on a definition of the SCS’s geographic limits that includes the Taiwan Strait, the Gulf of Tonkin, and the Natuna Sea.) China has never explained definitively what the dashed line signifies.

The South China Sea. CRS graphic.

In the northern part of the SCS, China, Taiwan, and Vietnam contest sovereignty of the Paracel Islands; China has occupied them since 1974. In the southern part of the sea, China, Taiwan, and Vietnam claim all of the approximately 200 Spratly Islands, while Brunei, Malaysia, and the Philippines, a U.S. treaty ally, claim some of them. Vietnam controls the greatest number. In the eastern part of the sea, China, Taiwan, and the Philippines all claim Scarborough Shoal; China has controlled it since 2012. China’s “nine-dash line” and Taiwan’s similar “eleven-dash line” overlap with the theoretical 200-nautical-mile (nm) EEZs that five Southeast Asian nations—Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Vietnam—could claim from their mainland coasts under the 1994 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). Indonesia disputes China’s assertions of maritime rights near its coast.

Dispute over Freedom of the Seas

A dispute over how to interpret UNCLOS lies at the heart of tensions between China and the United States over the activities of U.S. military vessels and planes in and over the SCS and other waters off China’s coast. The United States and most other countries interpret UNCLOS as giving coastal states the right to regulate economic activities within their EEZs, but not the right to regulate navigation and overflight through the EEZ, including by military ships and aircraft. China and some fellow SCS claimants hold that UNCLOS allows them to regulate both economic activity and foreign militaries’ navigation and overflight through their EEZs. In recent years, the U.S. Navy and Air Force have stepped up the pace and public profile of their activities in the South China Sea. The U.S. Navy conducts Freedom of Navigation Operations (FONOPs), challenging maritime claims that the United States considers to be excessive. It also seeks to maintain an ongoing presence in the SCS “to uphold a free and open international order,” while the U.S. Air Force flies bomber missions over the SCS. China regularly conducts military patrols and training in the SCS, and objects strenuously to U.S. military activities there. PRC officials regularly say that U.S. presence operations in the SCS undermine regional peace and stability.

A PRC Foreign Ministry spokesperson said in 2021 that such operations are “nothing but the ‘freedom of trespassing’ enjoyed by [U.S. military aircraft and ships] in saber-rattling and making provocations.” China and the other SCS claimants (except Taiwan, which is not a member of the United Nations) are parties to UNCLOS. The United States is not a party, but has long had a policy of abiding by UNCLOS provisions relating to maritime disputes and rights. UNCLOS allows state parties to claim 12-nm territorial seas and 200-nm EEZs around their coastlines and “naturally formed” land features that can “sustain human habitation.” Rocks that are above water at high tide but not habitable generate only territorial seas.

China’s Artificial Island Building

Between 2013 and 2015, China undertook extensive land reclamation in the SCS’ Spratly Island chain. According to the U.S. Department of Defense (DOD), the reclamation created over 3,200 acres (five square miles) of artificial landmasses on the seven disputed sites that China controls. China built military infrastructure on the outposts, and beginning in 2018, deployed advanced anti-ship and antiaircraft missile systems and military jamming equipment. China portrays its actions as part of an effort to play catchup to other claimants, several of which control more Spratlys features and carried out earlier reclamation and construction work on them, although the scale of China’s reclamation work and militarization has greatly exceeded that of other claimants. DOD’s 2022 report on PRC military and security developments stated that the Spratly Island outposts “allow China to maintain a more flexible and persistent military and paramilitary presence in the area,” which “improves China’s ability to detect and challenge activities by rival claimants or third parties and widens the range of response options available to Beijing.”

UNCLOS and the SCS

In 2013, the Philippines sought arbitration under UNCLOS over PRC actions in the SCS. In July 2016, an UNCLOS arbitral tribunal ruled that China’s nine-dash line claim had “no legal basis.” It also ruled that none of the land features in the Spratlys is entitled to any more than a 12-nm territorial sea; three of the Spratlys features that China occupies generate no entitlement to maritime zones; and China violated the Philippines’ sovereign rights by interfering with Philippine vessels, damaging the maritime environment, and engaging in reclamation work on a feature in the Philippines’ EEZ. The United States has urged China and the Philippines to abide by the ruling, which under UNCLOS is binding on both parties. China, however, declared the ruling “null and void.” China and the 10-member Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) are negotiating a Code of Conduct (COC) for parties in the SCS. Many observers believe that a binding COC is unlikely, and that China has prolonged the negotiations to buy time to carry out actions aimed at further strengthening its position in the SCS.

U.S. Actions

Several U.S. Administrations have sought to address tensions in the SCS. In 2020, the Commerce Department added to its Entity List PRC construction, energy, and shipbuilding companies involved in the SCS, barring U.S. companies from exporting to the firms without a government license. Biden Administration officials have regularly stated objections to PRC actions. In August 2022, Secretary of State Antony Blinken told incoming Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. that under the United States-Philippines Mutual Defense Treaty, the United States would assist Philippine forces in the event of a South China Sea contingency. The United States has stepped up security cooperation with Japan, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, and Vietnam; undertaken joint patrols in the SCS with other partners, including Japan, India, and Australia; and expressed support for other multilateral actions in the region. The Quadrilateral Security Dialogue—a grouping of the United States, Japan, Australia, and India—announced in May 2022 an effort to improve maritime domain awareness throughout the IndoPacific, including the SCS.

Select Legislation

Under a security assistance program currently known as the Indo-Pacific Maritime Security Initiative authorized by Congress in the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) for Fiscal Year (FY) 2016 (P.L. 114-92) and modified in the NDAAs for FYs 2017, 2019, 2022, and 2023, the United States has sought to improve the ability of regional countries to enhance maritime domain awareness (MDA) and patrol their EEZs.

The William M. (Mac) Thornberry National Defense Authorization Act for FY2021 (P.L. 116-283) established a Pacific Deterrence Initiative to strengthen U.S. defense posture in the Indo-Pacific region, addressing issues such as those in the SCS. The act included a statement that China’s “baseless territorial claims,” including in the SCS, “are destabilizing and inconsistent with international law.” Congress extended and expanded the Pacific Deterrence Initiative in subsequent NDAAs.

This article was republished in California as a work of the United States government from the Congressional Research Service to point warfighters and national security professionals to reputable and relevant war studies literature. Read the updated article with footnotes.

Ben Dolven, specialist in Asian affairs • Caitlin Campbell, analyst in Asian affairs • Ronald O’Rourke, specialist in naval affairs.

Related Articles

President Marcos Jr. Meets With President Biden—But the U.S. Position in Southeast Asia is Increasingly Shaky

Over a four-day visit to Washington, Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. has been welcomed to the White House and generally feted across Washington. With President Biden, Marcos Jr. (whose father was forced out of office in part through U.S. pressure, and whose family has little love for the United States) affirmed that the two countries are facing new challenges, and Biden said that “I couldn’t think of a better partner to have than [Marcos Jr.].”

The U.S. is about to blow up a fake warship in the South China Sea—but naval rivalry with Beijing is very real and growing

As part of a joint military exercise with the Philippines, the U.S. Navy is slated to sink a mock warship on April 26, 2023, in the South China Sea.

The live-fire drill is not a response to increased tensions with China over Taiwan, both the U.S. and the Philippines have stressed. But, either way, Beijing isn’t happy – responding by holding its own staged military event involving actual warships and fighter jets deployed around Taiwan, a self-governed island that Beijing claims as its own.