“God mode”, for those who aren’t gamers, is a mode of operation (or cheat) built into some types of games based around shooting things. In God mode you are invulnerable to damage and you never run out of ammunition.

What killer robots mean for the future of war

What killer robots mean for the future of war

What killer robots mean for the future of war

You might have heard of killer robots, slaughterbots or terminators – officially called lethal autonomous weapons (LAWs) – from films and books. And the idea of super-intelligent weapons running rampant is still science fiction. But as AI weapons become increasingly sophisticated, public concern is growing over fears about lack of accountability and the risk of technical failure.

Already we have seen how so-called neutral AI have made sexist algorithms and inept content moderation systems, largely because their creators did not understand the technology. But in war, these kinds of misunderstandings could kill civilians or wreck negotiations.

For example, a target recognition algorithm could be trained to identify tanks from satellite imagery. But what if all of the images used to train the system featured soldiers in formation around the tank? It might mistake a civilian vehicle passing through a military blockade for a target.

Why do we need autonomous weapons?

Civilians in many countries (such as Vietnam, Afghanistan and Yemen) have suffered because of the way global superpowers build and use increasingly advanced weapons. Many people would argue they have done more harm than good, most recently pointing to the Russian invasion of Ukraine early in 2022.

Don’t let yourself be misled. Understand issues with help from experts

In the other camp are people who say a country must be able to defend itself, which means keeping up with other nations’ military technology. AI can already outsmart humans at chess and poker. It outperforms humans in the real world too. For example, Microsoft claims its speech recognition software has an error rate of 1 percent compared to the human error rate of around 6 percent. So it is hardly surprising that armies are slowly handing algorithms the reins.

But how do we avoid adding killer robots to the long list of things we wish we had never invented? First of all: know thy enemy.

What are Lethal Autonomous Weapons (LAWs)?

The US Department of Defence defines an autonomous weapon system as: “A weapon system that, once activated, can select and engage targets without further intervention by a human operator.”

Many combat systems already fit this criteria. The computers on drones and modern missiles have algorithms that can detect targets and fire at them with far more precision than a human operator. Israel’s Iron Dome is one of several active defence systems that can engage targets without human supervision.

While designed for missile defence, the Iron Dome could kill people by accident. But the risk is seen as acceptable in international politics because the Iron Dome generally has a reliable history of protecting civilian lives.

There are AI enabled weapons designed to attack people too, from robot sentries to loitering kamikaze drones used in the Ukraine war. LAWs are already here. So, if we want to influence the use of LAWs, we need to understand the history of modern weapons.

The rules of war

International agreements, such as the Geneva conventions establish conduct for the treatment of prisoners of war and civilians during conflict. They are one of the few tools we have to control how wars are fought. Unfortunately, the use of chemical weapons by the US in Vietnam, and by Russia in Afghanistan, are proof these measures aren’t always successful.

Worse is when key players refuse to sign up. The International Campaign to Ban Landmines (ICBL) has been lobbying politicians since 1992 to ban mines and cluster munitions (which randomly scatter small bombs over a wide area). In 1997 the Ottawa treaty included a ban of these weapons, which 122 countries signed. But the US, China and Russia didn’t buy in.

Landmines have injured and killed at least 5,000 soldiers and civilians per year since 2015 and as many as 9,440 people in 2017. The Landmine and Cluster Munition Monitor 2022 report said:

Casualties…have been disturbingly high for the past seven years, following more than a decade of historic reductions. The year 2021 was no exception. This trend is largely the result of increased conflict and contamination by improvised mines observed since 2015. Civilians represented most of the victims recorded, half of whom were children.

Despite the best efforts of the ICBL, there is evidence both Russia and Ukraine (a member of the Ottawa treaty) are using landmines during the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Ukraine has also relied on drones to guide artillery strikes, or more recently for “kamikaze attacks” on Russian infrastructure.

Our future

But what about more advanced AI enabled weapons? The Campaign to Stop Killer Robots lists nine key problems with LAWs, focusing on the lack of accountability, and the inherent dehumanisation of killing that comes with it.

While this criticism is valid, a full ban of LAWs is unrealistic for two reasons. First, much like mines, pandora’s box has already been opened. Also the lines between autonomous weapons, LAWs and killer robots are so blurred it’s difficult to distinguish between them. Military leaders would always be able to find a loophole in the wording of a ban and sneak killer robots into service as defensive autonomous weapons. They might even do so unknowingly.

We will almost certainly see more AI enabled weapons in the future. But this doesn’t mean we have to look the other way. More specific and nuanced prohibitions would help keep our politicians, data scientists and engineers accountable.

For example, by banning:

- black box AI: systems where the user has no information about the algorithm beyond inputs and outputs

- unreliable AI: systems that have been poorly tested (such as in the military blockade example mentioned previously).

And you don’t have to be an expert in AI to have a view on LAWs. Stay aware of new military AI developments. When you read or hear about AI being used in combat, ask yourself: is it justified? Is it preserving civilian life? If not, engage with the communities that are working to control these systems. Together, we stand a chance at preventing AI from doing more harm than good.

This article was republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Jonathan Erskine is an aerospace engineer who, after a few years in the UK defence industry, has gone on to study Interactive AI at the University of Bristol.

Miranda Mowbray is a lecturer at the University of Bristol, where her research interests include cyber security and big data ethics. Miranda Mowbray’s research interests include cyber security and big data ethics. She did industrial research at HP for many years, particularly on computer privacy and security. She has also worked in academia, for example she helped to set up the University of Bristol’s PhD programme in Interactive AI. She has given conference / workshop talks on her research in over 15 countries. Miranda’s PhD is in Algebra, from London University. She is a Fellow of the British Computer Society.

Related Articles

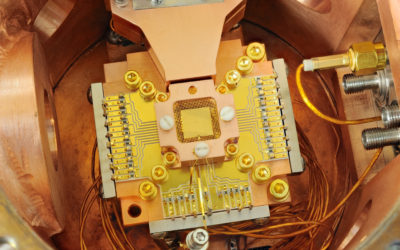

Understanding the building blocks for Australia’s quantum future

Australia is undergoing an exciting period of strategic technology policy review and development. The release of its first National Quantum Strategy this week committed the government to building the world’s first error-corrected quantum computer. This is a strategically important technology that has the potential to improve productivity and supply chain efficiency in diverse industries, lower costs across the economy, help reduce carbon emissions and improve public transportation.

Japan needs stronger deterrence than its new defense strategy signals

Since World War II, Japan had long chosen not to possess long-range strike capabilities that could be used against enemy bases. But the Japanese government changed course in December 2022 when it adopted the new national defense strategy (NDS), which included a commitment to acquiring a so-called counterstrike capability. But in order for this new strategy to contribute to deterrence and alter the nation’s defensive role as the ‘shield’ in its alliance with the United States, Tokyo needs to go further than what the NDS outlines.