“God mode”, for those who aren’t gamers, is a mode of operation (or cheat) built into some types of games based around shooting things. In God mode you are invulnerable to damage and you never run out of ammunition.

Japan Ditches Attack Helicopters: Will Australia Do the Same?

Japan Ditches Attack Helicopters: Will Australia Do the Same?

Japan Ditches Attack Helicopters: Will Australia Do the Same?

France invented the attack helicopter in 1956. Sixty-seven years later, Japan has decided that the idea has had its day.

‘Elimination of obsolete equipment’ is the cruelly decisive headline above photos of a Bell AH-1 Cobra and a Boeing AH-64D Apache, both attack helicopters, in a Japanese Ministry of Defense policy update published in December.

Uncrewed aircraft will replace them. The reason isn’t budget stress. On the contrary, plenty of money would have been available for the ministry’s formerly planned Cobra replacement program, because Japan is doubling its defence budget’s share of the economy.

This further calls into question Australia’s 2021 decision to renew the Australian Army’s attack helicopter force by buying 29 Apaches of the AH-64E version.

If fact, the Australian government and Department of Defence already may have lost interest in placing an immediate order.

Japan is also getting rid of scout helicopters—essentially, light attack helicopters that put more design emphasis on sensors instead of firepower. This decision is less radical than ditching helicopters for the attack mission, since reconnaissance and surveillance are among the first tasks shifted to uncrewed vehicles of any kind.

Japan will begin operating uncrewed replacements for attack helicopters this year, says the Yomiuri newspaper, citing several unnamed official sources. General deployment is to follow in 2025, the Yomiuri has said.

The 48 Cobras were already due for retirement. The ministry assessed possible crewed replacements for them in 2018 but omitted acquisition from its defence plan for 2019–2023.

Judging from reported plans for the trials, replacements will include loitering munitions (also referred to internationally as ‘kamikaze drones’). There will also be ordinary reusable drones of various sizes, such as have been appearing in armies in greater numbers for decades, often taking over the roles of crewed helicopters.

Australia’s intended order for Apaches has been part of the army’s plan to thoroughly re-equip itself for intense combined-arms ground combat.

As the risk of a maritime and air war involving China has become Australia’s overwhelming security concern, the army’s costly equipment plans have looked ever less relevant.

Now we have the judgement of Japan, a close friend, that attack helicopters are not worthwhile even for its capability requirements, which include land fighting to defend territory.

The attack helicopter was invented when the French Army, fighting in Algeria, took a step beyond simply bolting machine guns onto rotorcraft airframes. In 1956 it variously equipped Alouette II light utility choppers with anti-tank missiles or unguided rockets. Two years later, Bell Helicopter in the US saw that an ideal helicopter configuration for the attack mission would include a slim body with two crew members sitting in tandem; the US Army ordered the concept into production in 1966 as the AH-1.

The Australian Army didn’t participate in this revolution until 2004, when it began taking deliveries of 22 Airbus Tigers. They were so troublesome that they did not become fully operational until 2016 but since then have been performing well. The former government decided to replace them with Apaches.

Weapon categories rarely become suddenly obsolete. Usually, they progressively lose application as people devise increasingly effective countermeasures to them. In the fight to stay relevant, they often become more elaborate and costly. In some cases, a new, cheaper weapon category appears as a replacement.

All that has been happening to the attack helicopter. Short-range weapons for use against fleeting, low-level air targets have improved—and these weapons are largely designed to knock down jet aeroplanes flying several times faster than helicopters. Even unsophisticated guns and rockets intended for ground targets can be alarmingly effective against helicopters.

As lessons from wars such as the Iraq conflict 20 years ago have sunk in, decisions on the use of attack helicopters have become more prudent, meaning that sometimes they’re not used at all.

Russian attack helicopters have suffered badly in Ukraine. The Royal United Services Institute in London finds that at least 37 were lost between the 24 February invasion and 7 November last year.

Portable air-defence systems, or manpads, imposed heavy losses on attack helicopters that penetrated Ukrainian-held territory on search and destroy missions, RUSI says. Russia resorted to keeping such rotorcraft on its own side of the battle area, from where they could safely lob rockets.

No doubt Japan would imagine that its Apaches and the formerly planned Cobra replacements, if it had bought them, would have performed better than Russia’s attack helicopters—but not well enough, it seems.

Attack helicopters have also become more complex as armies have demanded more robustness, situational awareness, and weapon range, for safety. Compared with the Cobra, which is smaller, the Apache is an astonishingly high-performance machine.

And the cost these days? Well, the budget for Australia to buy 29 Apaches and make them operational is more than $5.5 billion—$190 million each.

Meanwhile, cheap battlefield drones are proliferating. They’ve also suffered badly in Ukraine, but they’re much cheaper and don’t have anyone in them when they crash. The Turkish-made Baykar Bayraktar TB2 drone, with a gross weight of 700 kilograms, reportedly costs US$1–2 million. For fair comparison with the Australian Apache acquisition, we could double that figure to include the cost of making them operational, with weapons, training and so on.

All this doesn’t mean that the attack helicopter is useless or that drones can replace it in every mission. But each of the trends discussed here is undermining its competitiveness in terms of value for money.

Japan has evidently judged that the competitiveness has now been damaged too much.

One aspect of its decision should stand out for Australia. Tokyo did not conclude that attack helicopters would still be viable if they had the highest capability available—which is to say, if they were AH-64Es. And it took that view even though its possession of 12 AH-64Ds would have greatly cut the cost of introducing the newer version.

That newer version is precisely the one that Australia decided on.

In May 2022, then–prime minister Scott Morrison said the government had ‘finalised’ the ‘investment’ to acquire AH-64Es.

But is Australia still planning to purchase new crewed attack helicopters at all?

In preparing this article, I asked the Defence Department about the status of the AH-64E program.

Defence did not provide an answer, not even a ‘no comment’, which would be most unusual for a program of no great secrecy that was proceeding more or less as intended. The department may be awaiting the outcome of the government’s defence strategic review.

Republished from the Australian Strategic Policy Institute under a Creative Commons license in the Commonwealth of Australia. Read the original article.

Bradley Perrett is a defense and aerospace journalist. He was based in Beijing from 2004 to 2020.

Related Articles

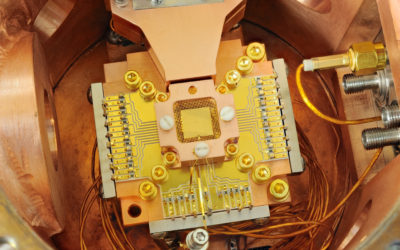

Understanding the building blocks for Australia’s quantum future

Australia is undergoing an exciting period of strategic technology policy review and development. The release of its first National Quantum Strategy this week committed the government to building the world’s first error-corrected quantum computer. This is a strategically important technology that has the potential to improve productivity and supply chain efficiency in diverse industries, lower costs across the economy, help reduce carbon emissions and improve public transportation.

Japan needs stronger deterrence than its new defense strategy signals

Since World War II, Japan had long chosen not to possess long-range strike capabilities that could be used against enemy bases. But the Japanese government changed course in December 2022 when it adopted the new national defense strategy (NDS), which included a commitment to acquiring a so-called counterstrike capability. But in order for this new strategy to contribute to deterrence and alter the nation’s defensive role as the ‘shield’ in its alliance with the United States, Tokyo needs to go further than what the NDS outlines.