“God mode”, for those who aren’t gamers, is a mode of operation (or cheat) built into some types of games based around shooting things. In God mode you are invulnerable to damage and you never run out of ammunition.

InfoSwarms: Drone Swarms and Information Warfare

InfoSwarms: Drone Swarms and Information Warfare

InfoSwarms: Drone Swarms and Information Warfare

Abstract

Drone swarms, which can be used at sea, on land, in the air, and even in space, are fundamentally information-dependent weapons. No study to date has examined drone swarms in the context of information warfare writ large. This article explores the dependence of these swarms on information and the resultant connections with areas of information warfare—electronic, cyber, space, and psychological—drawing on open-source research and qualitative reasoning. Overall, the article offers insights into how this important emerging technology fits into the broader defense ecosystem and outlines practical approaches to strengthening related information warfare capabilities.

Drone swarms are here. In Israel’s 2021 conflict with Gaza, the country’s military became the first to deploy a drone swarm in combat. During the ongoing conflict between Russia and Ukraine, Russia deployed the Kalashnikov KUB-BLA loitering munition, which reportedly is (or will be) capable of swarming. Russia also possesses a yet-to-be-deployed Lancet-3 munition with the potential capability to create aerial minefields to target drones and other aircraft.

The United States and its allies and adversaries are pursuing collaborative drone-swarm technology. This pursuit is no surprise. Drone swarms have applications for every military service across every area of conflict, from infantry support and logistics to nuclear deterrence. Military leaders across the Joint force must consider how drone swarms relate to existing capabilities and forms of warfare as the technology matures and enters the battlefield. These ideas should inform future concepts, acquisition decisions, exercises, training, plans, and operations to account for friendly and adversarial use. This article examines one aspect of a larger challenge: drone swarms and information warfare.

Although drone swarms may operate on land, at sea, in the air, and even in space, they are fundamentally information-dependent weapons. The common denominator of every swarm is the need to maintain stable communication links between drones and ensure information is processed efficiently and appropriately. Indeed, swarms are “multiple unmanned systems capable of coordinating their actions to accomplish shared objectives.” Many of the unique strengths of swarming also derive from information sharing.

The advantages of drone swarms stem from three key areas: swarm size, customization, and diversity. Each area depends on effective information management. Larger swarms with more sensors and munitions are more capable and can enable mass attacks; however, the swarm must handle inputs from more drones. Flexible swarms add or remove drones to meet commander needs, may break into smaller groups to attack from multiple directions or strike different targets, and handle changes to information inputs as drones are added or removed. Diverse swarms can incorporate different types of munitions and sensors and allow closely integrated, multidomain strikes, add new types of information sources, and create coordination challenges when the drones move at different speeds with different environmental risks. Information failure means risk of collision and loss of capability.

These capabilities enable novel tactics supported by information sharing. As Paul Scharre writes, “Swarming will be a more effective, dynamic, and responsive organizational paradigm for combat.” Swarms can concentrate fire on targets or disperse and reform to counterattack. Achieving these feats requires high levels of stable communication.

Support technologies depend on information as well. Machine vision—the ability of machines to see—requires a high volume of data to train the algorithms. Sensor drones use these algorithms to collect and share information on adversarial defenses, possible targets, and environmental hazards. Like individual drones, the swarm as a whole or the external control systems must process the high volume of information collected in the field. Processing speeds affect the swarm’s battlefield value because slower algorithm speeds mean slower decision making. Although a swarm may not incorporate machine vision, human controllers will face similar challenges as the swarm scales in size.

Information dependence means drone swarms must be considered in the context of information warfare. According to the Congressional Research Service, the US government does not have an official definition for information warfare. Practitioners typically define information warfare as “strategy for the use and management of information to pursue a competitive advantage, including both offensive and defensive operations.” This strategy includes electronic warfare, elements of cyberwarfare, and psychological warfare. Space warfare is included here because position, navigation, timing information, and satellite-based communication are critical information sources for unmanned systems.

Of course, noting the information dependence does not mean actors will successfully recognize or exploit this dependency. Although the Russian military has long recognized the importance of electronic warfare in countering drones, the military appears to have struggled in implementing this knowledge during the Ukraine conflict. For example, video released on social media seems to show Ukrainian drones in close proximity to Russian vehicles with no Russian electronic-warfare protection. The Russian military and others may also struggle to implement this knowledge in the cyber, space, and psychological warfare domains.

This article examines the relationship of drone swarms to the four dimensions of information warfare (electronic, cyber, space, and psychological) and explores artificial intelligence (AI) and robotics, which support the other areas and affect drone-swarm information-warfare vulnerabilities. Policy recommendations conclude the article.

This article was republished in California as a work of the United States government from the United States Army War College to point warfighters and national security professionals to reputable and relevant war studies literature. Read the report along with footnotes.

Zachary Kallenborn is a policy fellow at the Schar School of Policy and Government, a research affiliate of the Unconventional Weapons and Technology program at the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism, a senior consultant at ABS Group, and officially proclaimed US Army “mad scientist.” He is the author of publications on autonomous weapons, drone swarms, weapons of mass destruction, and terrorism involving weapons of mass destruction.

This article does not constitute endorsement of Analyzing War by the author.

Related Articles

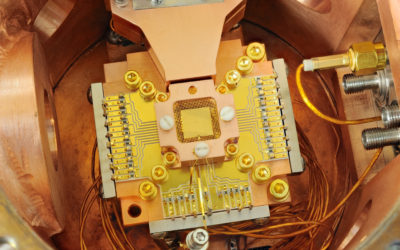

Understanding the building blocks for Australia’s quantum future

Australia is undergoing an exciting period of strategic technology policy review and development. The release of its first National Quantum Strategy this week committed the government to building the world’s first error-corrected quantum computer. This is a strategically important technology that has the potential to improve productivity and supply chain efficiency in diverse industries, lower costs across the economy, help reduce carbon emissions and improve public transportation.

Japan needs stronger deterrence than its new defense strategy signals

Since World War II, Japan had long chosen not to possess long-range strike capabilities that could be used against enemy bases. But the Japanese government changed course in December 2022 when it adopted the new national defense strategy (NDS), which included a commitment to acquiring a so-called counterstrike capability. But in order for this new strategy to contribute to deterrence and alter the nation’s defensive role as the ‘shield’ in its alliance with the United States, Tokyo needs to go further than what the NDS outlines.