“God mode”, for those who aren’t gamers, is a mode of operation (or cheat) built into some types of games based around shooting things. In God mode you are invulnerable to damage and you never run out of ammunition.

Hypersonic Weapons: Background and Issues for the United States Congress

Hypersonic Weapons: Background and Issues for the United States Congress

Hypersonic Weapons: Background and Issues for the United States Congress

The United States has actively pursued the development of hypersonic weapons—maneuvering weapons that fly at speeds of at least Mach 5—as a part of its conventional prompt global strike program since the early 2000s. In recent years, the United States has focused such efforts on developing hypersonic glide vehicles, which are launched from a rocket before gliding to a target, and hypersonic cruise missiles, which are powered by high-speed, air-breathing engines during flight. As former Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and former Commander of U.S. Strategic Command General John Hyten has stated, these weapons could enable “responsive, long-range, strike options against distant, defended, and/or time-critical threats [such as road-mobile missiles] when other forces are unavailable, denied access, or not preferred.” Critics, on the other hand, contend that hypersonic weapons lack defined mission requirements, contribute little to U.S. military capability, and are unnecessary for deterrence.

Funding for hypersonic weapons has been relatively restrained in the past; however, both the Pentagon and Congress have shown a growing interest in pursuing the development and near-term deployment of hypersonic systems. This is due, in part, to the advances in these technologies in Russia and China, both of which have a number of hypersonic weapons programs and have likely fielded operational hypersonic glide vehicles—potentially armed with nuclear warheads. Most U.S. hypersonic weapons, in contrast to those in Russia and China, are not being designed for use with a nuclear warhead. As a result, U.S. hypersonic weapons will likely require greater accuracy and will be more technically challenging to develop than nuclear-armed Chinese and Russian systems.

The Pentagon’s FY2023 budget request for hypersonic research is $4.7 billion—up from $3.8 billion in the FY2022 request. The Missile Defense Agency additionally requested $225.5 million for hypersonic defense. At present, the Department of Defense (DOD) has not established any programs of record for hypersonic weapons, suggesting that it may not have approved either mission requirements for the systems or long-term funding plans. Indeed, as Principal Director for Hypersonics (Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering) Mike White has stated, DOD has not yet made a decision to acquire hypersonic weapons and is instead developing prototypes to assist in the evaluation of potential weapon system concepts and mission sets.

As Congress reviews the Pentagon’s plans for U.S. hypersonic weapons programs, it might consider questions about the rationale for hypersonic weapons, their expected costs, and their implications for strategic stability and arms control. Potential questions include the following:

- What mission(s) will hypersonic weapons be used for? Are hypersonic weapons the most cost-effective means of executing these potential missions? How will they be incorporated into joint operational doctrine and concepts?

- Given the lack of defined mission requirements for hypersonic weapons, how should Congress evaluate funding requests for hypersonic weapons programs or the balance of funding requests for hypersonic weapons programs, enabling technologies, and supporting test infrastructure? Is an acceleration of research on hypersonic weapons, enabling technologies, or hypersonic missile defense options both necessary and technologically feasible?

- How, if at all, will the fielding of hypersonic weapons affect strategic stability?

- Is there a need for risk-mitigation measures, such as expanding New START, negotiating new multilateral arms control agreements, or undertaking transparency and confidence-building activities?

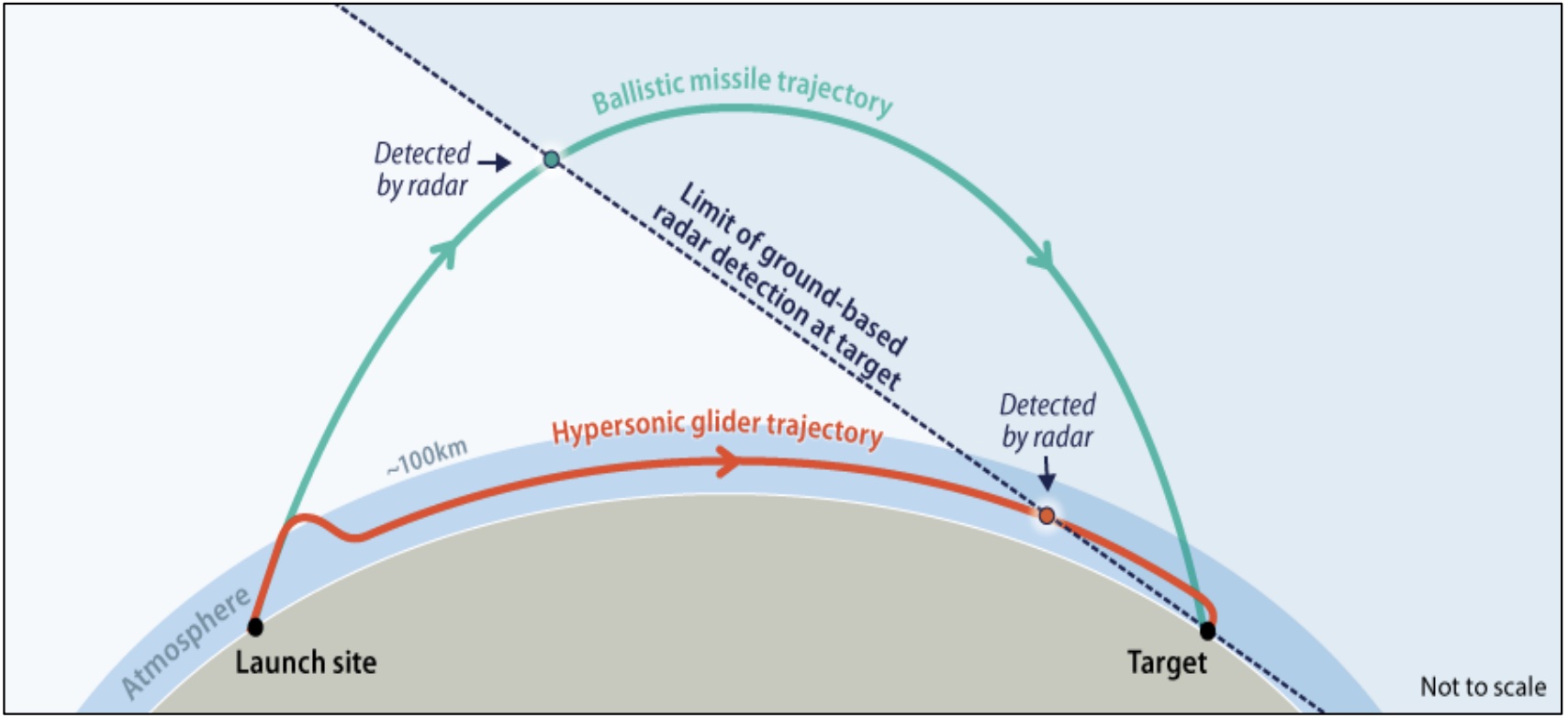

Terrestrial-Based Detection of Ballistic Missiles vs. Hypersonic GlideVehicles. CRS photo.

This excerpt was republished in California as a work of the United States government from the Congressional Research Service to point warfighters and national security professionals to reputable and relevant war studies literature. Read the original article.

Kelley M. Sayler is an analyst in advanced technology and global security for the U.S. Congress. This article does not constitute endorsement of Analyzing War by the author nor the U.S. Congressional Research Service.

Related Articles

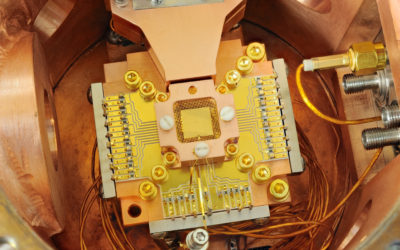

Understanding the building blocks for Australia’s quantum future

Australia is undergoing an exciting period of strategic technology policy review and development. The release of its first National Quantum Strategy this week committed the government to building the world’s first error-corrected quantum computer. This is a strategically important technology that has the potential to improve productivity and supply chain efficiency in diverse industries, lower costs across the economy, help reduce carbon emissions and improve public transportation.

Japan needs stronger deterrence than its new defense strategy signals

Since World War II, Japan had long chosen not to possess long-range strike capabilities that could be used against enemy bases. But the Japanese government changed course in December 2022 when it adopted the new national defense strategy (NDS), which included a commitment to acquiring a so-called counterstrike capability. But in order for this new strategy to contribute to deterrence and alter the nation’s defensive role as the ‘shield’ in its alliance with the United States, Tokyo needs to go further than what the NDS outlines.