“God mode”, for those who aren’t gamers, is a mode of operation (or cheat) built into some types of games based around shooting things. In God mode you are invulnerable to damage and you never run out of ammunition.

Governance Challenges of Transformative Technologies

Governance Challenges of Transformative Technologies

Governance Challenges of Transformative Technologies

Abstract

The rise of digital information and exponential technologies are transforming political/geopolitical, social, economic, and security arrangements. The challenges they pose to governance is unprecedented, distorting and used to manipulate public discourse and political outcomes. One of the most profound changes triggered by the unconstrained development of innovative technologies is the emergence of a new economic logic based on pervasive digital surveillance of people’s daily lives and the reselling of that information as predictive information.

EU responses to this new environment have been slow and inadequate. Establishing effective controls over the actors and processes harnessing innovative technologies will require not only specialized data governance skills but a deeper understanding of the impact of these technologies, the forging of partnerships across the public-private divide, and the establishment of greater political and social accountability of corporate actors involved in their development and application.

Introduction

The rise of innovative technologies is having a transformative impact on contemporary society. Two types of technologies stand out. The first is digital information and telecommunications, which has been developing ever more rapidly since the 1980s and is now entering the fifth-generation cellular wireless, or 5G, enabling better connectivity and transfer of larger amounts of data than ever. The second cluster of technologies, although differently engineered, are collectively defined as “exponential technologies” due to their unprecedented rate of technical progress. They include advanced robotics and drones, augmented and virtual reality, 3D printing, biotech, blockchain, the Internet of Things (IoT), autonomous vehicles and, of course, machine learning, which is also known as Artificial Intelligence (AI).

The new technologies have already found many applications for enhancing safety and security. They also have disrupted traditional ways of sharing information and have possibly undermined democratic principles and processes. They are the ultimate game-changer, globally disrupting existing political, economic, and security arrangements, empowering certain actors while subverting or overturning long-established governance processes and control regimes.

The scale of challenges posed to governance is unprecedented and requires a heightened understanding of the fundamental impact new technologies have on our social, political, economic, and geopolitical spheres. It is also imperative that policymakers and those who assist them develop a much deeper technological awareness and interest in exerting effective controls over the actors and processes by which these technologies are harnessed.

Innovative Technologies and Security

The new technologies are ‘data-hungry,’ gathering and producing enormous and ever-increasing amounts of data and posing significant challenges to effective government control over the instruments of national security and even the executive’s ability to control their own agents in the security sector. Traditionally, data was fragmented and managed in data silos. But the accelerated data-generating technologies of today demand a different management model founded on data security and cross-sectoral, holistic approaches to data governance. Moreover, the safe use of exponential technologies in any security domain requires supplying reliable data to responsible agencies.

Therefore, governments need to acquire skills in data governance alongside traditional governance practices. Some government agencies have recently begun moving from data centers to cloud computing. However, industry sources suggest that public authorities in many countries have resisted moving government data to the cloud and only 10-20 percent of government work uses the cloud, a sign that many governments are poorly prepared for this qualitative change.

Innovative technologies of today do not have the same properties as the systems of the past. Among the critical elements are small pieces of hardware such as processors, graphics cards, and miniature webcams, or intangibles such as dedicated software, algorithms, or technical know-how associated with machine learning and AI development. Moreover, these innovative technologies tend to be dual-use. For example, a drone equipped with day and night vision cameras and a radar for use in geological mapping surveys can become an instrument for military or law enforcement surveillance by simply changing the end-user. Similarly, while encryption of telecommunications data is necessary to protect business or security operations from competitive intelligence, it may also be used to conceal organized criminal activity from an investigation by law enforcement agents. And machine intelligence that has been employed to refine internet browser search platforms can also be applied to the means of warfare, from data fusion to autonomous unmanned weapons systems and cyberwar. Such factors make the most advanced technologies difficult to control by traditional export control regimes.

To make matters more complicated, artificial Intelligence turns technologies into “black boxes” that, intentionally or not, maybe opaque even to experts. Non-specialists in governments and society may, for all intents and purposes, be technically illiterate vis-à-vis AI-based devices, raising further challenges to their effective governance and control. AI specialists are quickly becoming one of the most sought-after resources in the new global economy.

Their importance in driving further innovation and their concentration in a handful of the largest global tech firms are becoming an issue of national well-being in the coming decades and a component of geopolitical competition, particularly with China. In a recent example, the President of the United States issued the Executive Order on Maintaining American Leadership in Artificial Intelligence. Among other things, the Order provides for changes in immigration policy, allowing to recruit and retain specialists in the field of AI development – yet another sign of the importance of long-term technological leadership.

As there will be many different actors working on transformative technologies across the public and private sectors, new tools of security governance are needed that can encompass non-governmental actors and commercial actors in the shaping of national security.

Thus, the governments of today need to find ways to cooperate effectively with large private enterprises, small startups, NGOs, universities, research institutes, and even individuals. Only in such a way can they keep abreast of developments and yield a degree of influence and control over the activities of the private entities if they constitute a threat to the country’s national security or political stability.

This excerpt was republished under a Creative Commons license to point warfighters and national security professionals to reputable and relevant war studies literature. Read the original article here.

Agnieszka Gogolewska is an e-learning consultant, scenario writer, academic lecturer, and author. Since 2010 she is a Senior Lecturer at the European University of Information Technology and Economics in Warsaw. Her main research interests are in democratic transitions and security sector reform, processes of democratization and de-democratization, intelligence and security studies. Dr. Marina Caparini is a Senior Researcher and Director of the Governance and Society Programme at SIPRI. Her research focuses on peacebuilding and the nexus between security and development. Marina has conducted research on diverse aspects of security and justice governance in post-conflict and post-authoritarian contexts, including police development, intelligence oversight, civil-military relations, and the regulation of private military and security companies. She has recently focused on police peacekeeping and capacity-building, forced displacement, and organized crime. Prior to joining SIPRI in December 2016, she held senior positions at the Norwegian Institute for International Affairs, the International Center for Transitional Justice, and the Geneva Centre for the Democratic Control of Armed Forces. E-mail: marina.caparini@sipri.org

Related Articles

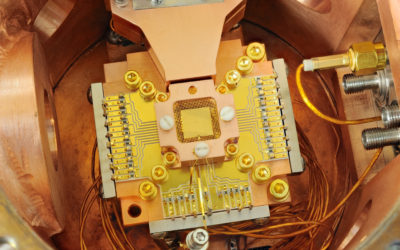

Understanding the building blocks for Australia’s quantum future

Australia is undergoing an exciting period of strategic technology policy review and development. The release of its first National Quantum Strategy this week committed the government to building the world’s first error-corrected quantum computer. This is a strategically important technology that has the potential to improve productivity and supply chain efficiency in diverse industries, lower costs across the economy, help reduce carbon emissions and improve public transportation.

Japan needs stronger deterrence than its new defense strategy signals

Since World War II, Japan had long chosen not to possess long-range strike capabilities that could be used against enemy bases. But the Japanese government changed course in December 2022 when it adopted the new national defense strategy (NDS), which included a commitment to acquiring a so-called counterstrike capability. But in order for this new strategy to contribute to deterrence and alter the nation’s defensive role as the ‘shield’ in its alliance with the United States, Tokyo needs to go further than what the NDS outlines.