More than 86 million Americans use the social media app TikTok to create, share, and view short videos, featuring everything from cute animals and influencer advice to comedy and dance performances.

Concerned experts point out that TikTok’s parent company, the Beijing-based ByteDance, has been accused of working with the Chinese government to censor content and could also collect sensitive data on users.

Darknet markets generate millions in revenue selling stolen personal data, supply chain study finds

Darknet markets generate millions in revenue selling stolen personal data, supply chain study finds

Darknet markets generate millions in revenue selling stolen personal data, supply chain study finds

It is common to hear news reports about large data breaches, but what happens once your personal data is stolen? Our research shows that, like most legal commodities, stolen data products flow through a supply chain consisting of producers, wholesalers and consumers. But this supply chain involves the interconnection of multiple criminal organizations operating in illicit underground marketplaces.

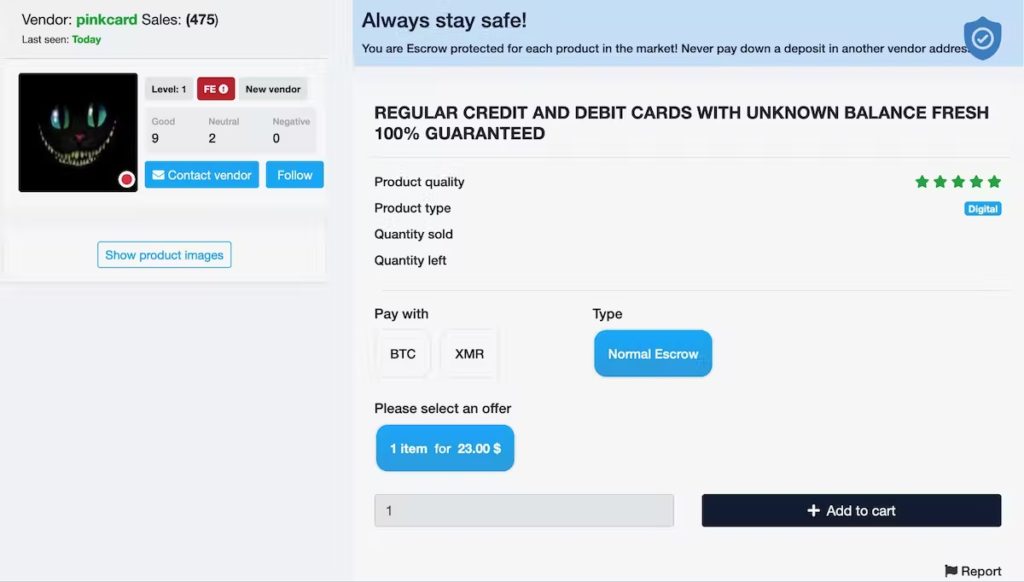

The stolen data supply chain begins with producers – hackers who exploit vulnerable systems and steal sensitive information such as credit card numbers, bank account information and Social Security numbers. Next, the stolen data is advertised by wholesalers and distributors who sell the data. Finally, the data is purchased by consumers who use it to commit various forms of fraud, including fraudulent credit card transactions, identity theft and phishing attacks.

This trafficking of stolen data between producers, wholesalers and consumers is enabled by darknet markets, which are websites that resemble ordinary e-commerce websites but are accessible only using special browsers or authorization codes.

We found several thousand vendors selling tens of thousands of stolen data products on 30 darknet markets. These vendors had more than US$140 million in revenue over an eight-month period.

The stolen data supply chain, from data theft to fraud. Christian Jordan Howell, CC BY-ND

Darknet markets

Just like traditional e-commerce sites, darknet markets provide a platform for vendors to connect with potential buyers to facilitate transactions. Darknet markets, though, are notorious for the sale of illicit products. Another key distinction is that access to darknet markets requires the use of special software such as the Onion Router, or TOR, which provides security and anonymity.

Silk Road, which emerged in 2011, combined TOR and bitcoin to become the first known darknet market. The market was eventually seized in 2013, and the founder, Ross Ulbricht, was sentenced to two life sentences plus 40 years without the possibility of parole. Ulbricht’s hefty prison sentence did not appear to have the intended deterrent effect. Multiple markets emerged to fill the void and, in doing so, created a thriving ecosystem profiting from stolen personal data.

Example of a stolen data ‘product’ sold on a darknet market. Screenshot by Christian Jordan Howell, CC BY-ND

Stolen data ecosystem

Recognizing the role of darknet markets in trafficking stolen data, we conducted the largest systematic examination of stolen data markets that we are aware of to better understand the size and scope of this illicit online ecosystem. To do this, we first identified 30 darknet markets advertising stolen data products.

Next, we extracted information about stolen data products from the markets on a weekly basis for eight months, from Sept. 1, 2020, through April 30, 2021. We then used this information to determine the number of vendors selling stolen data products, the number of stolen data products advertised, the number of products sold and the amount of revenue generated.

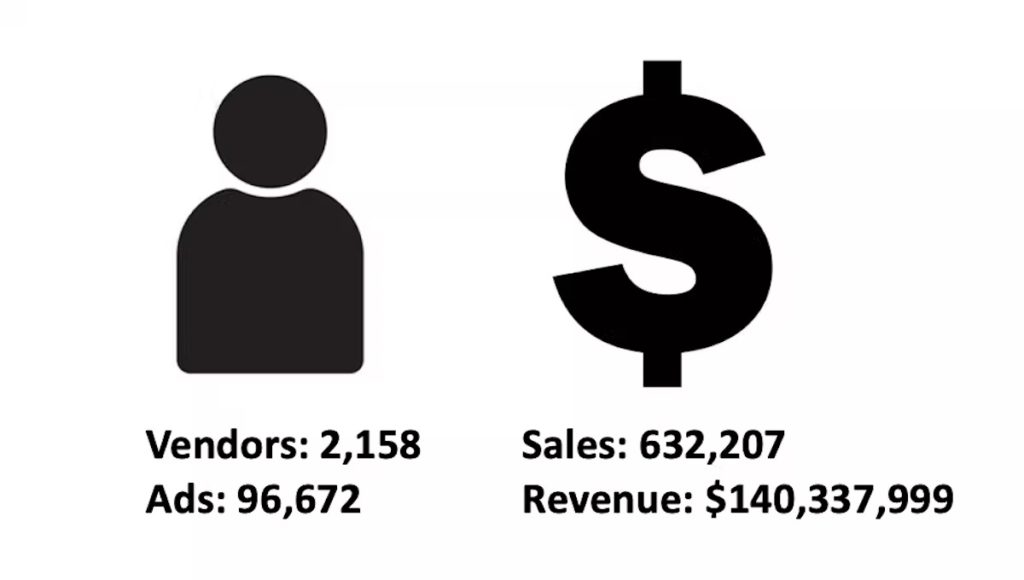

In total, there were 2,158 vendors who advertised at least one of the 96,672 product listings across the 30 marketplaces. Vendors and product listings were not distributed equally across markets. On average, marketplaces had 109 unique vendor aliases and 3,222 product listings related to stolen data products. Marketplaces recorded 632,207 sales across these markets, which generated $140,337,999 in total revenue. Again, there is high variation across the markets. On average, marketplaces had 26,342 sales and generated $5,847,417 in revenue.

The size and scope of the stolen data ecosystem over an eight-month period. Christian Jordan Howell, CC BY-ND

After assessing the aggregate characteristics of the ecosystem, we analyzed each of the markets individually. In doing so, we found that a handful of markets were responsible for trafficking most of the stolen data products. The three largest markets – Apollon, WhiteHouse and Agartha – contained 58% of all vendors. The number of listings ranged from 38 to 16,296, and the total number of sales ranged from 0 to 237,512. The total revenue of markets also varied substantially during the 35-week period: It ranged from $0 to $91,582,216 for the most successful market, Agartha.

For comparison, most midsize companies operating in the U.S. earn between $10 million and $1 billion annually. Both Agartha and Cartel earned enough revenue within the 35-week period we tracked them to be characterized as midsize companies, earning $91.6 million and $32.3 million, respectively. Other markets like Aurora, DeepMart and WhiteHouse were also on track to reach the revenue of a midsize company if given a full year to earn.

Our research details a thriving underground economy and illicit supply chain enabled by darknet markets. As long as data is routinely stolen, there are likely to be marketplaces for the stolen information.

These darknet markets are difficult to disrupt directly, but efforts to thwart customers of stolen data from using it offers some hope. We believe that advances in artificial intelligence can provide law enforcement agencies, financial institutions and others with information needed to prevent stolen data from being used to commit fraud. This could stop the flow of stolen data through the supply chain and disrupt the underground economy that profits from your personal data.

This article was republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license to point warfighters and national security professionals to reputable and relevant war studies literature. Read the original article.

Dr. C. Jordan Howell is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Criminology at the University of South Florida. Dr. Howell’s research focuses on the human factor of cybercrime. He employs advanced computer science techniques to gather threat intelligence, which is then used to test the social scientific theory, build profiles of active cyber-offenders, plot criminal trajectories, and disrupt the illicit ecosystem enabling cybercrime incidents. He has published over 20 manuscripts, most of which pertaining to cybercrime and cybersecurity related issues. • David’s research interests include theories of human behaviors, cyber-enabled and cyber-dependent crimes and experimental research methods. In 2015 he was awarded the “Young Scholar Award” from the “White-Collar Crime Research Consortium of the National White-Collar Crime Center” for his cybercrime research. He is also the recipient of the “Philip Merrill Presidential Scholars Faculty Mentor Award” (from the University of Maryland), and the “Best Publication award in Mental Health” (from the American Sociological Association). Since being at Georgia State University, Dr. Maimon has created an Evidence-Based Cybersecurity Group where he and his researchers seek to produce empirical evidence and provide systematic reviews of existing empirical research and provide tools in preventing the development and progression of cyber-dependent crimes.

Related Articles

Pentagon leaks suggest China developing ways to attack satellites – here’s how they might work

The recent leak of Pentagon documents included the suggestion that China is developing sophisticated cyber attacks for the purpose of disrupting military communication satellites. While this is unconfirmed, it is certainly possible, as many sovereign nations and private companies have considered how to protect from signal interference.

Ransomware Attack Hits Marinette Marine Shipyard, Results in Short-Term Delay of Frigate, Freedom LCS Construction

The Wisconsin shipyard that builds the U.S. Navy’s Freedom-class Littoral Combat Ship and the Constellation-class guided-missile frigate suffered a ransomware attack last week that delayed production across the shipyard, USNI News has learned.

Fincantieri Marinette Marine experienced the attack in the early morning hours of April 12, when large chunks of data on the shipyard’s network servers were rendered unusable by an unknown professional group, two sources familiar with a Navy summary of the attack told USNI News on Thursday.